My Blog

Short blog posts to communicate ideas, share experiences on language teaching and learning and reflect on the profession overall. Your comments and feedback are highly appreciated.

eltea

Young Learners: Optimal conditions for language learning

- Children learn best when we set a safe and positive learning environment where they are encouraged to experiment and their contributions are acknowledged and valued. As teachers, we might not be responsible for the children’s aptitude towards the language but we can definitely influence their attitude towards it. We don’t want to associate bad experiences with language learning. Creating positive first learning experiences can only lead children into continuing learning in the future.

- Young learners benefit from multisensory learning. Kids are more likely to learn and retain information when they are engaged with materials using a variety of senses.

- Children are more likely to learn when they are engaged, motivated and challenged. Children can easily get motivated if the activity or experience is meaningful to them. Taking time to get to know your students (icebreakers/class profiles) and finding out what they are interested in is essential if you want to help them learn.

- Nurturing children’s curiosity is key to their learning. It’s this drive that leads to knowledge. Children who are curious are destined to succeed.

- Young children learn by themselves. There’s an early stage in their language development when they are learning in silence. During this time they are actively listening and working out the patterns of the language. Students are able to respond to the teacher's instructions, e.g. ‘Sit down', 'Open your books', but they remain silent as they do not yet feel ready to produce speech. A silent period is the first stage of language acquisition and it’s crucial for the teacher to respect this process and not force the child to produce speech. Teachers cannot speed up this process and it requires lots of patience on their behalf. Gently encouraging a kid to join in, but also giving them the time they need to observe is a delicate balancing act. More info here.

- Children learn through play. Play provides a great natural context for language development. We need to value play-based activities and the learning opportunities they offer and stop using games as a reward after children finish their class work.

- Children learn through songs and stories. Songs’ repetitive patterns enable children to memorize language and stories provide a great context and stretch students’ imagination.

- Children learn when they are encouraged to interact and cooperate with their peers. Based on Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, between the ages of 7-11, children drop their egocentric characteristics and they find it easier to co-exist and share with others.

- Young learners have a short attention span and can easily get distracted and bored. Using a variety of activities, and providing them with frequent brain breaks (5 min per hour) can help them cope with boredom. However, children can carry on for a long time as long as they are engaged and motivated, e.g. interesting play-based activities. In that case they are so engaged that they don’t even realize they use L2.

- Effective classroom management sets the stage for optimal learning. Establishing classroom routines helps them feel more secure as they know what they are expected to do.

Reflections on a year of CELTA training

The profile of course participants

Most of the people who take a CELTA course are looking for a career change or wish to travel and teach overseas. They usually have zero teaching experience and though during the interview they claim they realize the intensity of the course, they only do so fully once the course gets underway. What you will often hear them say is ‘I was told that it was hard but I never thought it would be this hard’. This is not a surprise, as most of them tend to think that language teaching involves having a conversation with the students to improve their English. Focusing on language clarification via a more communicative approach is a novel and mind-blowing idea to them. Still, once they comprehend what teaching involves, they are very trainable and willing to try new methods and approaches.

At the other end of the spectrum, there are trainees with lots of teaching experience who attend the course because they want to develop further or they just need the qualification to teach overseas. They usually join the course with their own set of fixed beliefs and assumptions which often rely on a more lecture-based style of instruction. This group is more sceptical to new approaches and ideas and therefore more reluctant to re-evaluate/question what they had been doing for such a long time and seemed to work for them. Unlearning what they already know is not easy and therefore their resistance to change is reasonable. Those who join the course with an open mind and a willingnes to embrace change tend to get a lot more from the experience. Unlearning requires lots of personal work and it takes time which sometimes they cannot afford in such an intensive course.

Responding to course participants’ affective needs

What most trainees struggle with is the workload of such an intensive course and how expectations change as the course unfolds. It’s a constant race and when they think they can see the finish line, new hurdles appear. This can be nerve-wracking and affects their self-confidence. I remember one of the trainees saying. ‘Once I have sorted out my instructions, I have to think of language clarification. And now I have to think about managing feedback’ He referred to it as a series of hardships he was overwhelmed with which often led to a lack of confidence and a great amount of self-doubt. Most trainees, whether they say it out loud or not, feel that way. It is also surprising how trainees tend to focus mainly on what they are not doing rather than celebrate their own progress no matter how small this might be. During feedback they mainly mention what they want to change in their lessons rather than things that went well and they should repeat. Maybe it’s human nature but it’s crucial to be able to spot their strengths and notice their progress. Another trap trainees fall into is comparing themselves with other teachers rather than focus on their progress from one lesson to the other. What I try to instil in teachers is that all of us, myself included, regardless of teaching experience have their own action points and these cannot be the same. Learning is an ongoing process for everyone.

Input sessions and experiential learning

Planning input sessions is also an integral part of the teacher training cycle and I have concluded that ‘less is more’. The first input sessions we run are usually packed with information and it’s only when we run a session a couple of times, we can get a sense of what can be covered at a certain amount of time. And though I have ‘stolen’ great ideas from colleagues, I prefer planning my own input sessions from scratch in my own style. By doing so, the delivery of the session becomes easier and more natural.

Without undermining the importance of theory, as a trainee myself, I had always thought that watching my own tutors demonstrating good teaching techniques during input was far more effective than telling me what to do. Putting trainees in the learners’ position during input by demonstrating activities and employing classroom management techniques that are immediately applicable in the teaching provides trainees with good models to follow. Experiential learning makes all these techniques not only more tangible but also more memorable. While observing lessons and seeing trainees mimicking my techniques and sometimes even my style, I wonder if I have encouraged ‘replicas’ of a more experienced teacher and whether I have stifled their creativity and their ability to think on their feet. Judging from my own experience, as a teacher, I think not. What teachers need at the very beginning is a framework to rely on. Once they get more teaching experience-more likely after the course- and have more time for self-reflection, they can move into a more critical reflection of their own practices and start deviating from the norm and what they know by experimenting even more.

Assessing lessons

Assessing lessons is another challenging aspect of the job. The criteria do offer the basic framework but their interpretation presents a serious challenge. The questions are similar to what we have been discussing. Is a lesson where the teacher follows standard procedures and implements mechanical techniques always a strong lesson? Do we ‘force’ teachers to go by the book/procedures? Are we more prescriptive than we should be? Do we train them on how to keep a balance between planned input and responsive teaching? For example, one of the criteria refers to ‘teaching a class with an awareness of the students’ needs’ and another that refers to ‘giving students appropriate practice.’ What if a teacher never went into practice, but they gradually helped students with the target language, allowed students to discover the language working at their own pace and gained more confidence? What if they are ready to use the language effectively but not during the lesson due to lack of time?

Still, is this possible with a group of teachers with limited or zero experience? Are we setting the bar a bit higher? Is this part of a more advanced training course? It might be better to encourage newly qualified teachers to conform to more standard procedures and through more teaching experience this might take its course. Despite CELTA being an in-service course, whenever there is a chance and depending on the personality of the trainees, which is also a key factor here, we can light the spark to become more critical professionals.

'The Future of Training' at IH London - YL & PBL: A framework for self-reflection and self-assessment for learners and teachers

On the 9th of November I had the pleasure of giving a talk at the ‘Future of Training’ at IH London. I had the chance to meet a bunch of highly motivated teachers and trainers and share ideas and beliefs. Among the things we discussed was how PBL can help students produce tangible results that they can relate or apply to their lives but also how we can convince teachers to adopt new methods and approaches.

Below you can see some of the key points of the talk as well as the link for the PowerPoint presentation.

https://www.dropbox.com/h?preview=IH+CONFERENCE+session.pptx

Many thanks to those who attended.

By adopting a PBL and creating a formatively driven classroom

- you are being proactive by sorting out problems during the project and not at the end of it

- you get inside the learners head and see what they are thinking

- you move learning forward by structuring your lesson according to the students’ needs and lacks

- you allow students to use their classmates as a resource for learning, promoting cooperative learning.

- you are building up a positive culture of confidence.

Understanding learners' Silent Period. Maximizing learning through TPR activities.

Total Physical Response (TPR) is an approach to second language teaching that was developed in the 1970s by James Asher who saw a resemblance between first and second language acquisition.

Asher noticed that children acquire their mother tongue mainly by observing their surroundings, listening to adults telling them what to do and performing actions accordingly without, however, speaking. For example, the parent says: ‘Give me the book’ and the children do so.

Similarly, in the early stages of second language learning, students respond to the teacher's instructions, e.g. ‘Sit down', 'Open your books', but they remain silent as they do not yet feel ready to produce speech.

Although learners are seemingly silent, there is a set of complex neurological connections being made in their brain and they are actively processing the language spoken to them. That stage might take a few weeks or even months and it’s crucial for the teacher to respect this process and not force the child to produce speech. We cannot speed up the process more than we can force a civil engineer to build a house in a few weeks. Patience is key at this stage. Additionally, some teachers might find it hard to discern whether a student goes through a silent period or there is something more serious that needs to be examined further. In that case, we need to evaluate the child’s responsiveness to simple instructions. If the child can follow simple instructions, it’s a good indication that he/she is going through a silent period. If you suspect that there might be something more serious, you need to observe and notice more signs, such as lack of eye contact or lack of pointing. Most of the times parents and educators pick up learning difficulties during the early stages of first language acquisition, so it’s a good idea to liaise with them and compare your observations.

A silent period is indeed the first stage of second language learning. However, rarely do educators or linguistics refer to a silent period at any other stage of the second language acquisition, which, based on my experience so far, is also possible.

Throughout the years, I have observed learners of different ages who are not necessarily beginners go through the same silent phase. This might be so, because they have their own, sometimes unique way of internalizing language before they reach speech production. At other times, they tend to be so overwhelmed by a new language point that it takes more time for it to soak in. In either case, staying silent in class should not be frowned upon.

TPR activities are stirrers that can help us create a stress-free classroom environment where all students are valued and take part in the learning process without feeling intimidated. The students do not have to say any words. Comprehension becomes the first step to language acquisition. They only have to listen to instructions and understand what to do. For example, the teacher can read a student’s daily routine and ask the learners to perform the actions. Children often see it as a game but, as it has already been discussed, it’s a lot more.

TPR activities can be set up very easily, with minimal amount of preparation required. Of course, if you want to enhance the experience, you can incorporate props or costumes, which can make it seem more real and be more engaging. TPR is suitable for classes of all sizes (even individual students) although you need to consider the classroom space available in large classes.

Another great benefit of TPR is that it works well with mixed ability classes, creating an inclusive environment where even the weak students can copy the actions from the stronger students and complete the task.

TPR involves a lot of performance and movement, making language more memorable.

Below you can find some examples of TPR activities

TPR Activities

- Miming:

Split the class in two groups. Ask one member from each group to come at the front and mime a word that you have recently taught. The team that finds the word first gets the point.

- Narrators and Actors

Split the class in two groups. Some are the narrators and some are the actors. Choose a dialogue or story from your coursebook. The narrators read it out and the actors act it out.

- Talking Mirrors

Get the students in pairs. One child looks into the mirror (represented by the other child) and mimes actions from their daily routine. The other child (the mirror) mimes the action while saying what they are doing.

- Spot the mistake

Read a funny story to your students and ask them to mime it. Then, read the story again but this time with a few mistakes. Ask the students to bang their pencil on their desk or stand up if they hear a mistake.

Halloween Vocabulary Activity

The aim of the controlled activity is to check the meaning of the Halloween words that students have been introduced to, as well as have some Halloween fun.

1. Split your class into two groups.

2. Write the Halloween words you want your students to practise in small pieces of paper and put them in a bowl with some shredded paper.

3. A student from each team comes at the front. Place a desk between them and put the bowl in front of one of the students. The student picks a piece of paper with the Halloween word written on it (the shredded paper makes it more difficult) and describes it to his/her team without saying it. When they do find the word, the student pushes the bowl towards the other student who does the same. Meanwhile, let your students know that every now and then they will hear a bomb explode. When that happens and the bowl is on their side, they lose. Then, different members of their team come at the front and do the same.

(For the bomb explosion I use this one https://www.online-stopwatch.com/interval-timer/ by adding different duration time intervals. For example, the first one lasts 30 secs, the second one lasts 45 secs etc. Don’t forget to set the sound as well.)

Enjoy!

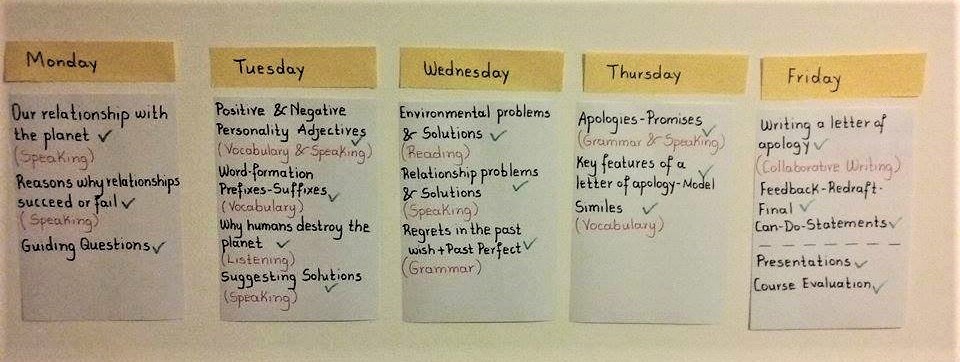

Project Based Learning and Teenagers. Demanding but rewarding. (An authentic one-week course with plan of work, materials and photos/slides from the lessons)

Anyone who has taught teenagers knows that they come with their own teaching challenges, such as lack of interest, poor discipline, scant attention and frequent mood swings. Teachers might work their fingers to the bones and still come up against a brick wall. Teaching teenagers is undeniably hard work and therefore they are not usually welcomed by most teachers.

However, before we get our pitchforks ready and label them as lazy and uncooperative, we, as teachers, ought to make an effort to understand them. We have all been in their place and we do remember all the sudden changes in our lives, mood and feelings. We were all quick to blame the hormones but neuroscience gives a further explanation. In her book ‘Why are teenagers so Weird?’ Barbara Strauch mentions that during adolescence the teenage brain undergoes great changes. The frontal part of the brain that is related to logic and emotions is being rewired during adolescence and the assumption that the reconstruction of the neurons is responsible for the teenagers’ lack of concentration and stubbornness seems valid.

Knowing the characteristics of this age group is an asset that enables the teachers to build bridges between themselves and their teenage learners and finally maximize language learning. Adopting a positive attitude and appropriate techniques can significantly influence the effectiveness of the learning process and offer a learning experience that learners can relate to.

One element that hinders constructive language learning among teenagers is the neglect of their needs and interests. As it has already been mentioned, what is often the case-mostly because of their rebellious nature-is the misconception that the students who are eager to learn, will and those who are unmotivated and indifferent won’t no matter what. However, the main aim of a teacher who works with teenagers is not only to inspire and involve those who seem disengaged but also to offer an enjoyable and rewarding learning experience to the students who seem more excited to learn and participate. When such factors are taken into consideration, teenagers can work wonders. The methodologist Penny Ur refers to teenagers as ‘the best language learners’ who if they are engaged , not only become passionate with what they do but they also feel committed to work harder and get the most out of the lessons.

Taking all the above into consideration and also the fact that teenagers like projecting themselves, looking for peer approval , we can assume that project based learning might be ideal for this age group. This is because project based learning is a personalized learning approach which focuses on the students’ personal interests and language needs. The students examine the language through topics that they themselves consider interesting and that alone can catch the students’ attention and turn them into more active learners. Once the teenage learners get engaged, language learning takes its course and the teacher acts as a facilitator and prompter.

Below I will present the framework of a one-week project based course with a group of 12 mid-Intermediate South American students, 8 female and 4 male aged from 15 to 17. Despite my initial concern that the project would fail for reasons I will explain below, it turned out to be a success.

This is how the week unfolded.

MONDAY

Although this was the first day of our project, it was not the first time I met the students as I had taught the exact same group the week before. They were a group of very lively and outgoing teenagers who were enjoying their first time in the UK during their school break. They were keen on learning but just like all teenagers they were also eager to mix with other nationalities, make new friends and flirt.

The school’s theme of the week ‘Planet Earth’ left them rather disappointed as later this week on Wednesday it was Valentine’s Day and they really did expect-surprisingly enough the boys did too-that the theme of the week would be around this holiday. Their reaction did not take me by surprise as they had been asking about Valentine’s day since the previous week. The school’s theme could not change but neither could the students’ interests be ignored.

On that first day the students reflected on our relationship with the planet and they concluded that although the planet takes care of us by providing us with the air we breathe, the water we drink and the soil that grows our food, we don’t appreciate it and we only cause harm. Next the students examined the relationships of couples, focusing on questions like the following. Do they always get along? Why do couples break up? Is it always a mutual decision? How can they save their relationship? Upon this topic the discussion got heated and the students had lots to say. Lots of opinions were heard and they boiled down to the conclusion that sometimes one of the two neglects/mistreats the other although the other doesn’t deserve it. The students were able to notice the parallel between the two cases and they agreed that our relationship with the planet resembles the relationship of a couple in which one is caring whereas the other one is thoughtless. The students even named the couple so throughout the week we would examine how Alan and Karen’s relationship was similar to our relationship with the planet.

As it has already been mentioned here http://eltea.org/blog/how-to-implement-project-based-learning-in-your-esl-classroom a project based course is framed by a guiding question and towards the end of the lesson we came up with these two: ‘How can a romantic relationship resemble our relationship with the planet? How can we compensate the planet for all the harm we have caused?’

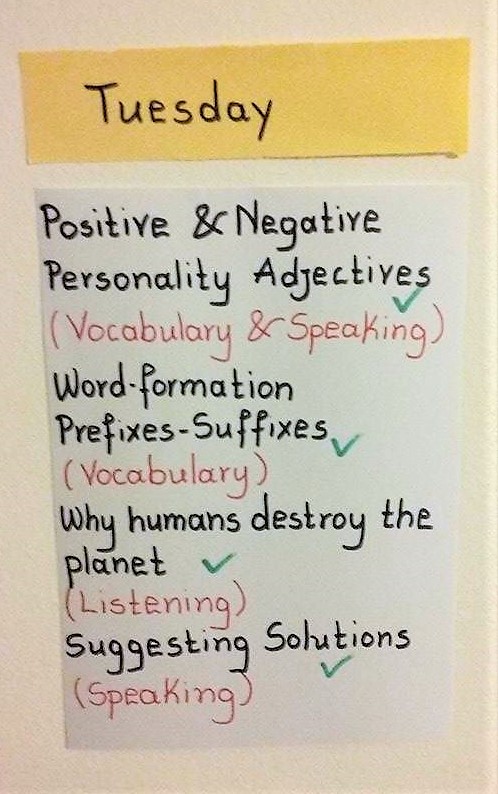

TUESDAY

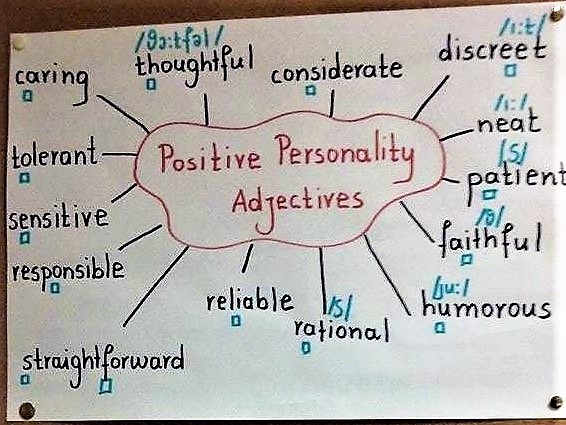

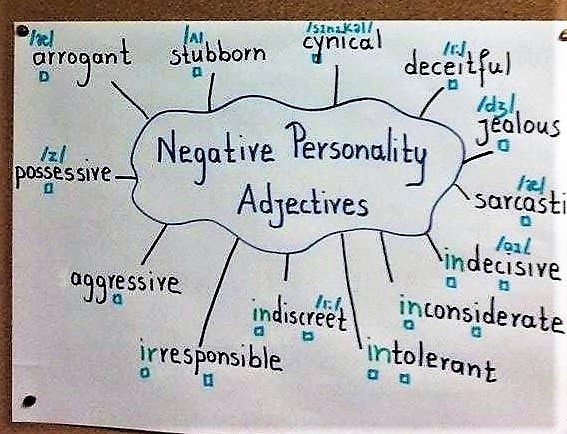

On Tuesday the students discussed what qualities people are looking for in a partner and they justified their answers by giving examples. The students revised personality adjectives, both positive and negative, and added new ones to their vocabulary. They also focused on the common prefixes and suffixes used to form adjectives and opposite words. Later the students used some of these adjectives to describe our relationship with the planet.

E.g.: We’ve been thoughtless and selfish because....

The students also noticed the repetitive use of the word ‘harmful’ and they looked up for synonyms to add to their notebooks, such as ‘disastrous’, ‘ferocious’, ‘vicious’, ‘inhumane’, ‘merciless’, ‘ruthless’.

During the second part of the lesson, the students watched a silent animated video that examines our relationship with the planet https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WfGMYdalClU . Based on what they saw, the students discussed how people harm the environment and brainstormed solutions. Finally, they listened to the audio of a video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gUhxcdzRgLQ where solutions were suggested and the students checked if they had similar or different ideas. If the students have problems, you can choose to show them the video as subtitles are also provided.

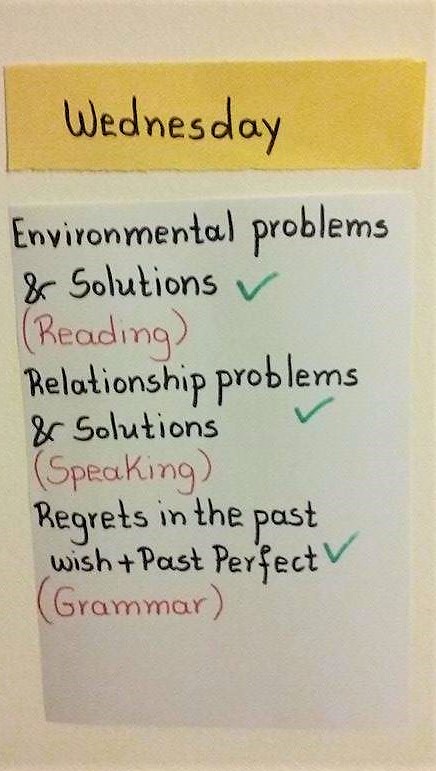

WEDNESDAY

On Wednesday the students read a text where they matched environmental problems to solutions in order to consolidate what they did the day before.

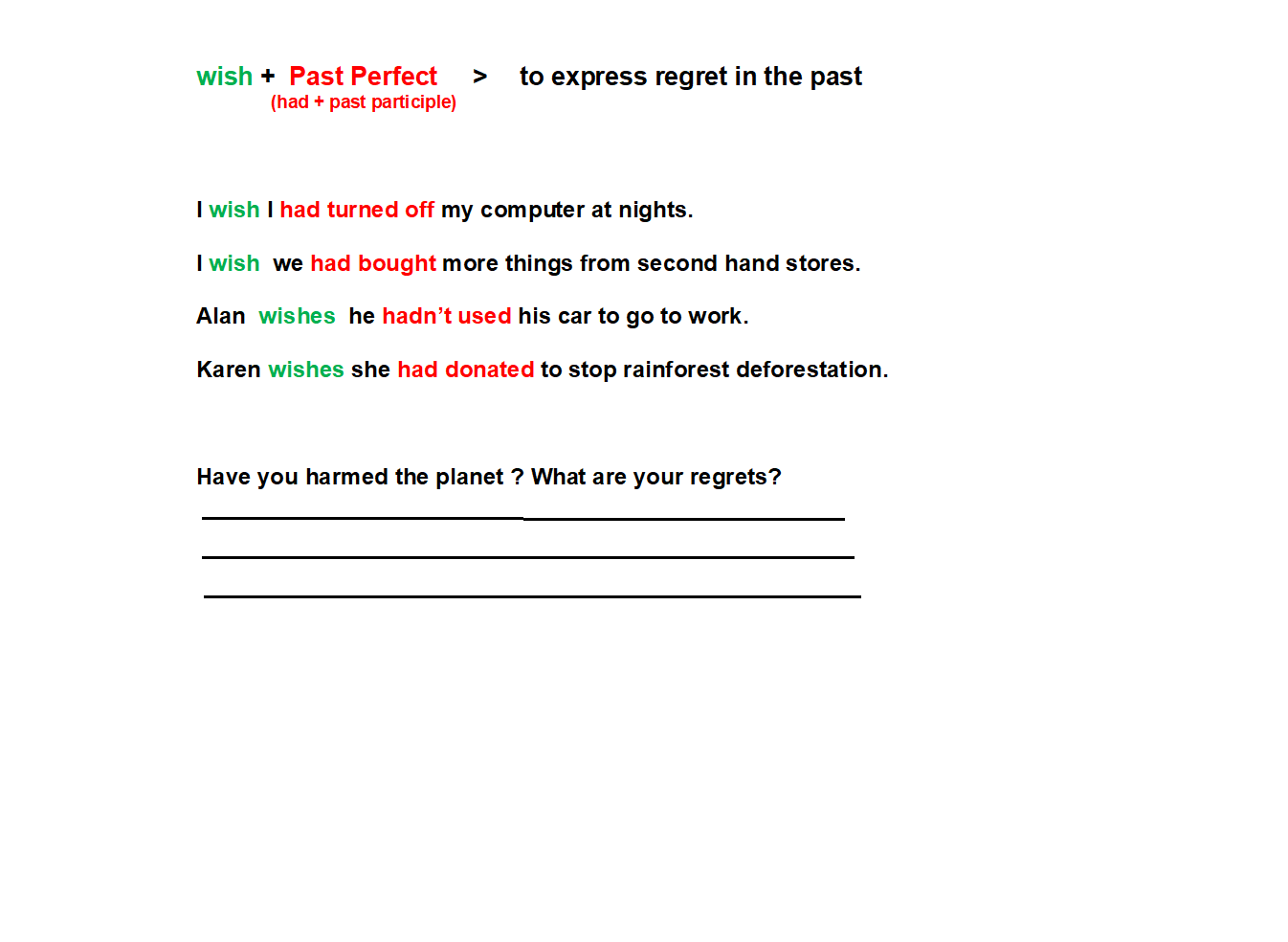

Next, the students brainstormed what problems couples usually face and what might be the possible solutions. For reasons of convenience, we also used the imaginary couple we created on Monday. Finally, the students examined how people can express regret in the past and produced examples both related to the planet and romantic relationships.

Examples

I wish I had recycled more.

I wish I had used energy efficient appliances

Alan wishes Karen had spent less money.

Karen wishes Alan hadn’t forgotten her birthday.

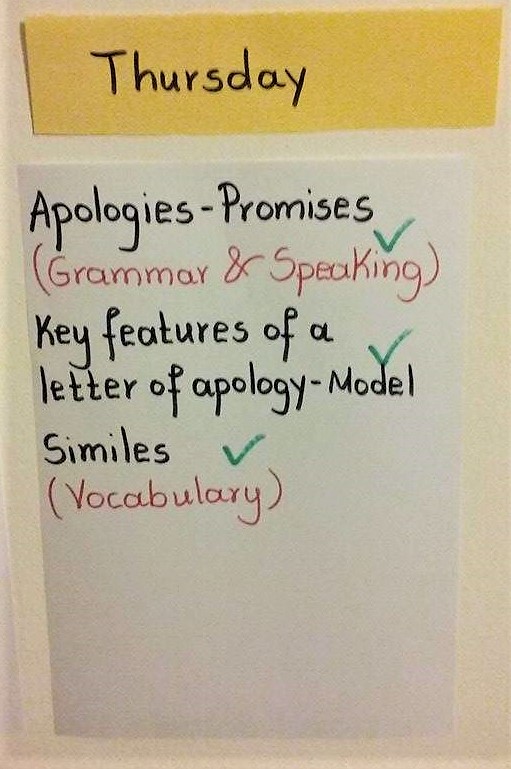

THURSDAY

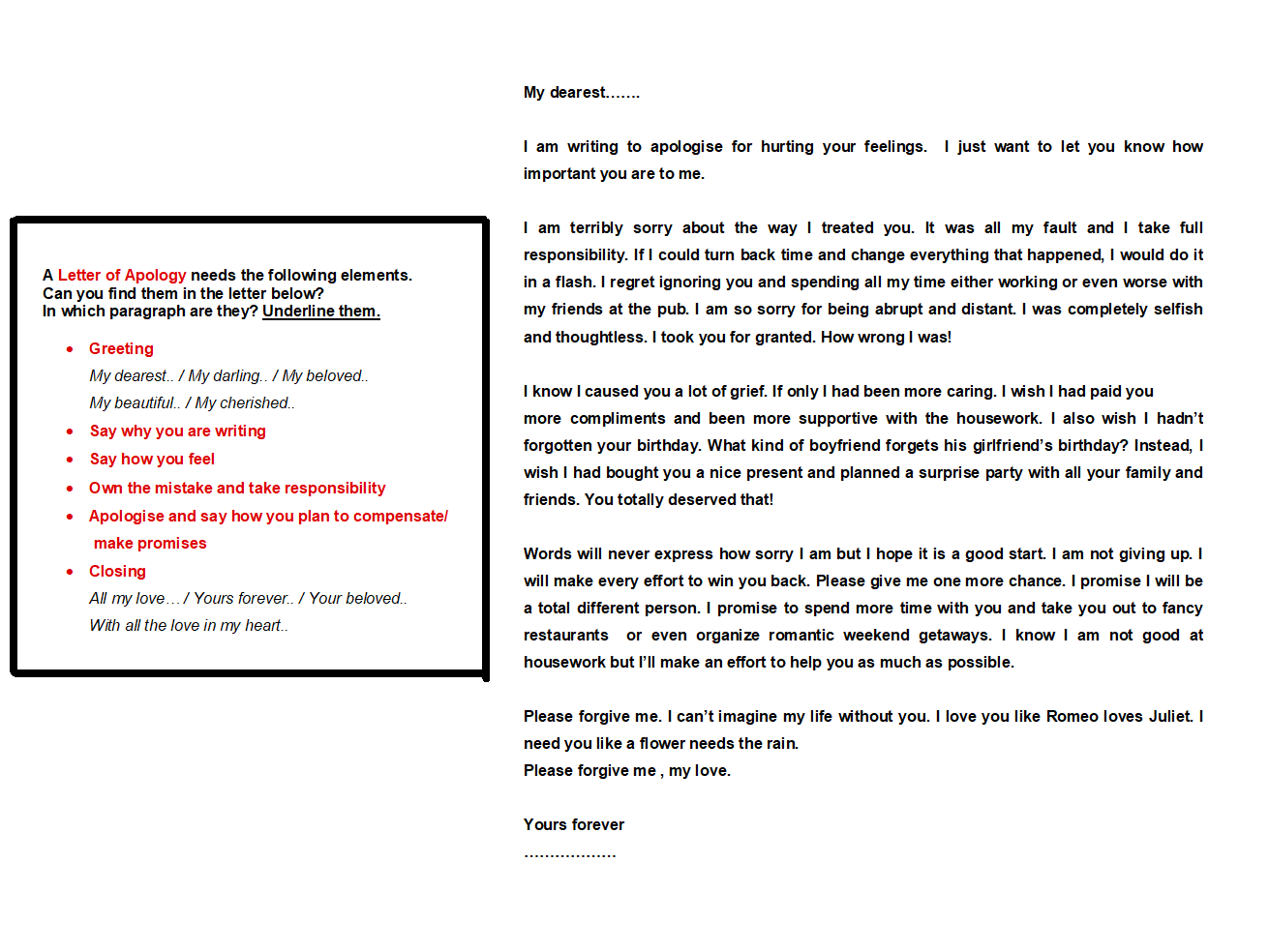

On Thursday the students practised how to apologise and make promises. Then they examined the key features of a letter of apology by looking at a model. Finally, the students practised expressing their feelings using similes.

FRIDAY

On Friday the students wrote in groups a letter of apology to the planet. They produced a first draft and they used the computer room to write the final letter which you can see below. It’s obvious that the students got creative by adding pictures and while some had a romantic approach, others chose a more humorous one.

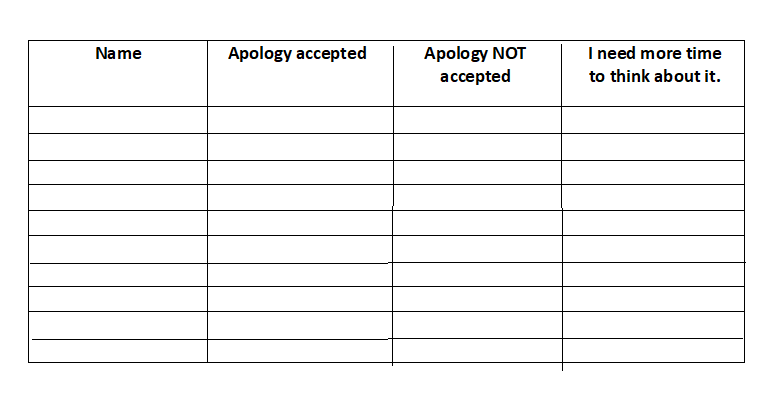

When the students from the other classes (the guests) came to see their project, they had to read the students’ letters and decide if they accept the apology or not or if they need more time to think.

Upon reflection one might argue that the final outcome is not a real world task as the PBL suggests it should be. In real life nobody would ever write a letter of apology to the planet. This is indeed a fair point. However, since in this case the interests of the students did not match the school’s theme, there were only two options. Either to ignore the students’ interests, something that totally contradicts the principles of PBL, or to slightly deviate from the norm. After all, although the students will never write that same letter in real life, the language they used in this letter is useful and applicable in real life. the students had fun working on their project and practised useful language items/functions that were also able to use for their final outcome.

There is no doubt that teenagers are a demanding age group but seeing their whole transformation and development taking place in front of your eyes makes it one of the most rewarding experiences in your teaching career. I do feel that teaching them has trained me to observe my learners before making any teaching decision and to develop as a teacher.

If you want to see a PBL course with young learners aged 6-10, have a look here http://eltea.org/blog/project-based-learning-young-learners-challenging-but-possible-an-authentic-one-week-course-with-plan-of-work,-materials-and-photos-from-the-lessons

Lesson Plan: Using Phrasal Verbs for relationships to talk about love stories (B1/B1+) 16+

The aim of the lesson is to enable students to use phrasal verbs to talk about their own love stories or the love stories of famous couples.The lesson plan includes all the materials used in the lesson.

Phrasal Verbs for Relationships (B1/B1+)

The handouts include matching exercises, speaking cards and gap filling exercises for further practice. For a full lesson plan on phrasal verbs for relationships see here:http://eltea.org/lesson-plans/lesson-plan-using-phrasal-verbs-for-relationships-to-talk-about-love-stories

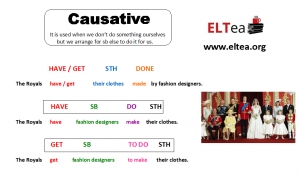

Lesson Plan: Introducing Causative Structures in the context of household chores B1+/B2

The aim of the lesson is to enable the students to use Causative structures in the context of household chores using scaffolding instruction.